For those who live in big cities and towns, it can be all too easy to forget just how much beautiful countryside the UK has to offer. And even for those who are holed up in so-called concrete jungles, it doesn’t take much travelling before you’re surrounded by the peace and tranquility of the country.

A big part of that luxury is down to the Green Belt.

What is the Green Belt?

For those unaware or unsure of what the Green Belt is exactly, it is a government policy introduced to curb urban growth or sprawl - essentially putting a ring of protected countryside around certain big towns and cities to stop them growing too big.

Originally, the Metropolitan Green Belt was established to slow the rapid growth of London, and was brought in by the Greater London Regional Planning Committee in 1935. Following this, the Town and Country Planning Act 1947 enabled local authorities to plan for green belt proposals of their own. There are now 14 green belts, covering roughly 13% of total land.

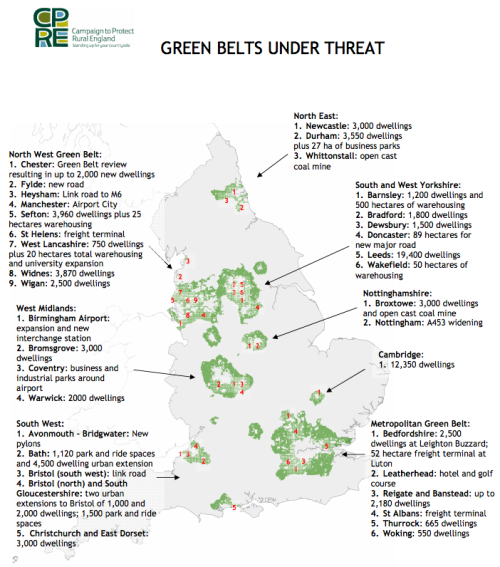

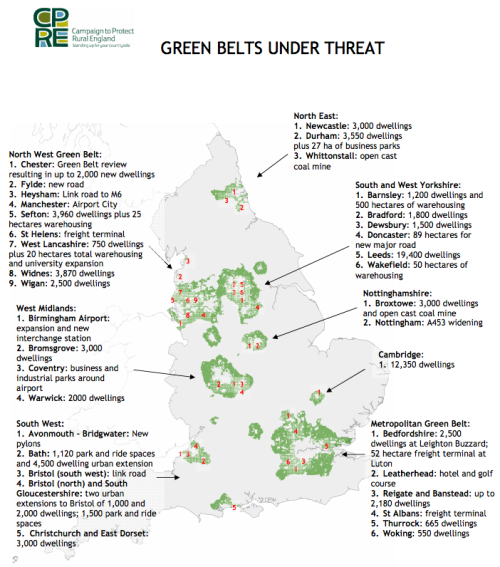

Since then, green belt land has been introduced around several other conurbations, including Birmingham, Manchester, Nottingham, Newcastle, Leeds, and Bristol. You can see where green belt land is located on the map below…

This interactive map on The Telegraph is also well worth a look, allowing you to see in more detail the location of green belt land in the UK.

Is the Green Belt under threat?

Despite all the best intentions, the Green Belt isn’t completely untouchable, and not only is it possible to build on that land, but the rate at which it’s happening is increasing.

The foremost authority on the changing face of green belt land is the Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE), and their research makes for very interesting reading.

The map below from 2012 shows examples of how and where green belt land is being built on around the country.

Image source: CPRE

And numbers of new dwellings are continuing to increase.

Data collected annually by CPRE has shown that there could be a genuine threat to the Green Belt if the rate of development continues to rise. In August 2012, there were 81,000 houses proposed on the Green Belt. By March 2016, this number had more than tripled, to 275,000.

Hertfordshire is one of the places currently feeling a good portion of the pressure, with 34,000 homes planned, and another 10,000 waiting for the green light, while a recent CPRE report found blueprints 123,000 homes in the Green belt around London.

These examples are being echoed around the country.

Why is the Green Belt being built on?

As you’ve probably already worked out, the reason the Green belt is being built on is a simple one - housing.

The long and short of it is that we simply don’t have enough affordable housing in this country to cope with the number of people who need it. The National Housing Federation estimated that nearly a million new homes needed to be built between 2011 and 2014, but a BBC investigation found that the number that were actually built was half this.

Henry Gregg, Assistant Director of Communications and Campaigns at the National Housing Federation, sent us this statement:

“We, as a nation, haven’t built enough houses for decades and are currently 100,000 short of the number we need to build each year. This is having a real impact on the lives of ordinary families who, faced with high housing costs, find themselves just managing. Having the right land available at the right price is a crucial factor in how many homes can be built and at what speed.“

Normally, green belt land can only be built on in ‘exceptional circumstances’, but the scale of the current housing crisis (or at least the perceived scale) is enough for authorities to grant using green belt land for housing exceptional status.

Paul Miner, Planning Campaign Manager at CPRE, explained it to us in a little more detail:

“Local councils are under pressure from the Government to set and meet very high targets for housebuilding – these targets often require an amount of housing that far surpasses actual local need. To stick to these targets, councils have to find the land to build houses on.

“Green Belt should be permanently protected from development except in ‘exceptional circumstances’, but councils claim that the need to meet their housing targets is an ‘exceptional circumstance’ that justifies releasing Green Belt land for development.”

However, Paul told us that there may be ulterior motives at play as to why green belt land is being build on rather than other types of land, specifically brownfield sites that have been built on previously.

“In many cases, profit is behind developers’ reluctance to build on brownfield land: simply put, building on green fields is more profitable and less difficult than building on brownfield. Brownfield sites may need clearing or decontaminating, which means up-front costs for the developer, and are often smaller, which means there is less scope to build the large homes that will make the most money.

“In some cases councils are also keen to remove land from the Green Belt for housing to increase their revenue. The Government’s ‘New Homes Bonus’ is paid to councils for all houses built in their area, and research suggests that this is driving the increased amount of planning permission given by councils, including in the Green Belt.”

Is the need for housing more important than the Green Belt?

Of course, not everyone shares the view of the CPRE. Martha Grekos, Head of Planning at law firm Howard Kennedy LLP, wrote in Property Week that the CPRE’s recommendations for protecting green belt land were “extremely unhelpful”.

Ms Grekos continued by saying that it’s important to distinguish between the different types of green belt land, that we need to “deconstruct the picture postcard myth of verdant fields and meadows open to all”, and suggesting that some of the land closer to built-up areas could be reclassified. The article states that 19,334 hectares of the 514,040 hectares in the London Metropolitan Green Belt are within a 10 minute walk of a train station, which apparently makes it “prime for development”.

Rather than just posing an issue for housing developers, the Green Belt itself has even been criticised for its role in the current housing crisis, blamed for pushing up house prices as the cost of land has increased over the years.

The CPRE, however, insist that green belt land simply isn’t the answer to the housing problems in the UK, and that brownfield sites are a much more appropriate solution. We’ll come onto this shortly.

Image credit: Tabs Taberham

The Green Belt is disappearing… so what?

If the Green Belt were to slowly dwindle away, would it really be the worst thing in the world? What effect would it really have?

Well this is still summed up very nicely by the main who introduced the Green belt policy in 1955, Duncan Sandys, Minister of Housing, who stated: “for the wellbeing of our people and for the preservation of the countryside, we have a clear duty to do all we can to prevent the further unrestricted sprawl of the great cities.”

It is this ‘unrestricted sprawl’ that is the largest issue according to the CPRE, who worry that without green belt land, we could eventually see a number of large towns merging into one another.

Paul Miner from CPRE: “To see the important work the Green Belt does we need only look to countries like America where there are no Green Belts around cities, and suburbs stretch out for miles. If the Green Belt continues to be reduced, we will start to see that kind of effect in this country, with cities sprawling out over the countryside.”

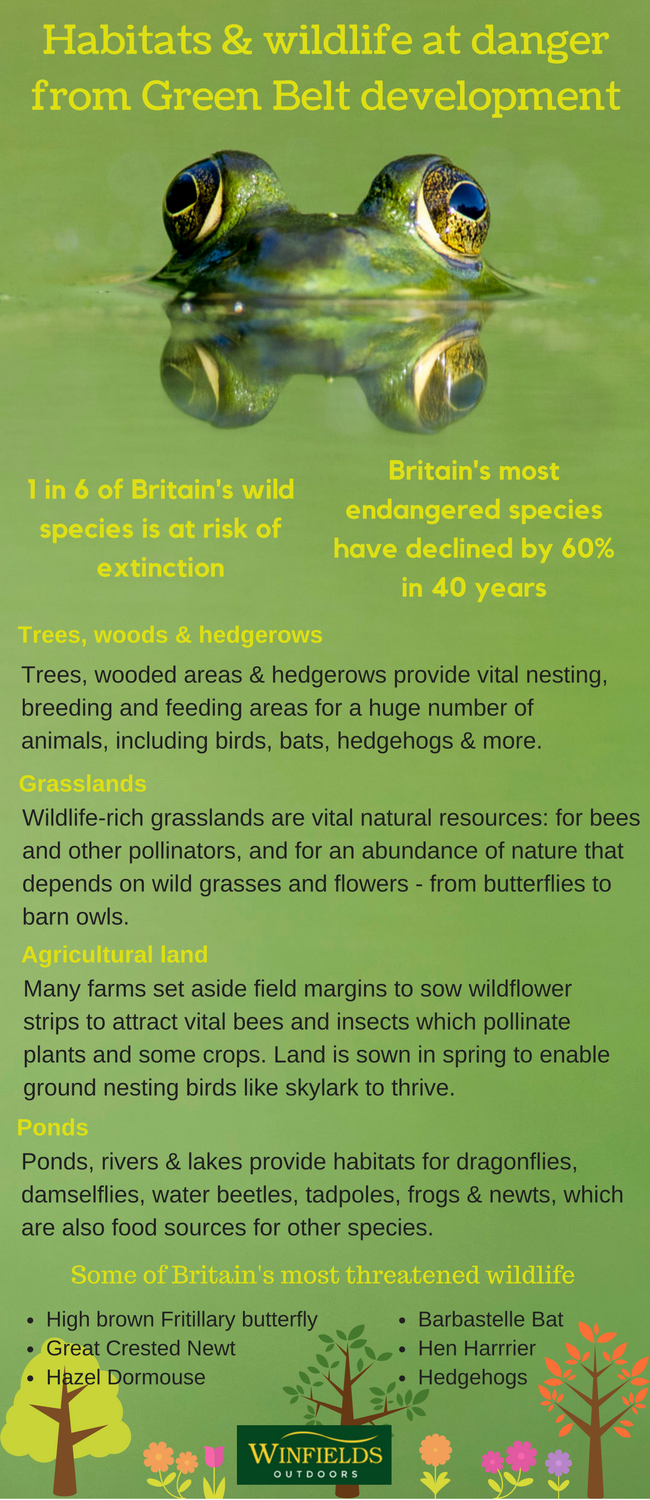

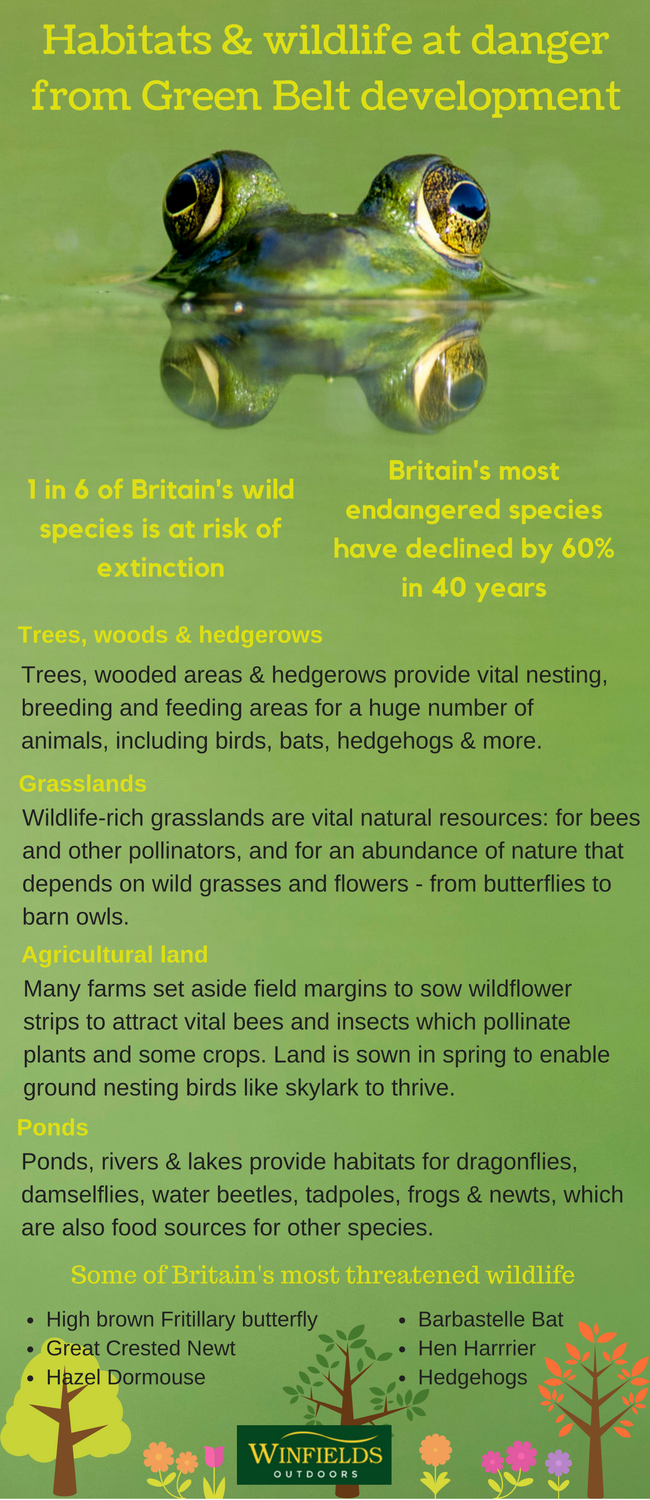

But that’s not the only issue. Green Belts give us 30,000 km of public rights of way, 89,000 ha of Sites of Special Scientific Interest and 220,000 ha of broadleaf and mixed woodland. That’s not to mention the football pitches, parks and other green spaces that could be at risk, as well as the need to build extra infrastructure to developments on Green Belt land, and the danger to countless wildlife habitats and ecosystems that could be destroyed.

The Wildlife Trust told Winfields: “Wildlife is under pressure on many fronts. Over the past 50 years we've seen declines in two thirds of the UK’s plant and animal species, for a range of reasons, including loss of habitat. Many of our common species - hedgehogs, sparrows, starlings and common frogs, for example – are increasingly endangered. Green Belt land is important because it’s home to a wide range of species - it can provide a wildlife highway for many animals, creating corridors for them to move between cities and towns and the wider countryside.

“And Green Belt land that’s open to the public, such as woods, nature reserves or footpaths through the countryside, provide a fantastic way to people who live in nearby towns to cities to enjoy nature close to where they live.”

Here are some of the habitats and animals that would be at risk if the Green Belt were to disappear…

Share this Image On Your Site

You can find more about planning and building on and around green spaces in this document from the Wildlife Trust.

What can be done to protect the Green Belt?

So what’s the solution? It’s no secret that we need housing in this country, but if we’re to protect Green Belt land, we need to come up with another solution. As we mentioned a little earlier in the article, CPRE believes that brownfield land is the answer.

They said: “Research conducted for CPRE by the University of the West of England has shown that there is space for at least one million homes on brownfield land in England. A recent CPRE report also showed that developments on brownfield land are completed more quickly than on greenfield sites, and academic studies have also shown that cleaning up contaminated brownfield land has public health benefits.

“To get more houses built, the Government needs to invest in brownfield development to encourage housebuilders to use these sites - rather than cherry-pick green fields in the Green Belt or elsewhere.”

However, the sticking point with this solution is, as is often the case, the cost. Brownfield land is space that has been previously used for industrial or commercial activity, and therefore costs more to redevelop. This poses a problem for developers looking to turn a profit.

According to estate agents Savills, it costs roughly £100 per square foot to build a new house on a ‘development-ready’ site, and that this house would need to sell for £200 per square foot to be financially viable. However, around 40% of houses that could potentially be built on brownfield sites would exceed this threshold, thus making development extremely unlikely, particularly in the South of England.

So what can the average person like you or me do to help protect the Green Belt? One way you can help is by making your views known on inappropriate developments near you - both by writing to your MP and by commenting on planning applications. You can find advice and guides from CPRE at planninghelp.cpre.org.uk.

CPRE has a local branch in every county in England, who work at a local level to protect their natural spaces. If you’d like to become more involved in the fight for a beautiful, thriving countryside, you can become a member of CPRE or volunteering with your local branch. You can find more details at www.cpre.org.uk.

What are your thoughts on protecting the Green Belt? Should we do everything in our power to save it or is the need for housing a more pressing concern?

Let us know in the comments below or get in touch on Facebook or Twitter.